- Getting started with HTTPS: Overview

- Getting started with HTTPS: Java keystore and keytool essentials

- Getting started with HTTPS: Let’s Encrypt on Cloud Foundry and Bluemix

- Getting started with HTTPS: Trusting Let’s Encrypt certificates in Java

If you are running a web application and it’s still not using HTTPS, shame on you! Even if you are not transmitting sensitive data, there are still several reasons why you should enable HTTPS.

In 2014, Google announced that HTTPS was a ranking signal for its search results. Protecting your user’s data, higher ranked in Google AND that nice green bar in front of your website? Still not convinced? On top of that we see that HTTP/2, which gives users a nice speed increase, is mostly supported in combination with HTTPS for now. What’s keeping you, partner?

It used to be expensive and tedious process getting a SSL certificate for your domain. If your site was not dealing with credentials or sensitive personal data you could say it wasn’t worth the effort. Nowadays, this is no longer an excuse not to get a certificate. With providers like SSLMate (paid) and initiatives like Let’s Encrypt (free), creating your certificate is a trivial task. Since Let’s Encrypt is a fully automated and free solution to get your certificates, a lot of people are using it.

In this blog series will try to explain a few things about HTTPS and show common tasks and problems you might run into. First I will go through a bit of terminology, so the following posts can be concise.

Terminology

TLS vs SSL

TLS is the successor to SSL. It is a protocol that ensures privacy between communicating applications. Unless otherwise stated, in these posts consider TLS and SSL as interchangable. The most secure and recent > version is TLS v1.3.

Certificate

You will see a lot of information about public and private key pairs when reading up on HTTPS/TLS. The certificate is the public key part, which can be freely given to anyone.

Private Key

A private key can verify that its corresponding certificate/public key was used to encrypt data. It is never given out publicly.

Certificate Authority (CA)

A company that issues digital certificates. For SSL/TLS certificates, there are a small number of providers like Symantec, Versign, Comodo, GoDaddy, LetsEncrypt, whose certificates are included by most browsers and Operating Systems. They serve the purpose of a “trusted third party”.

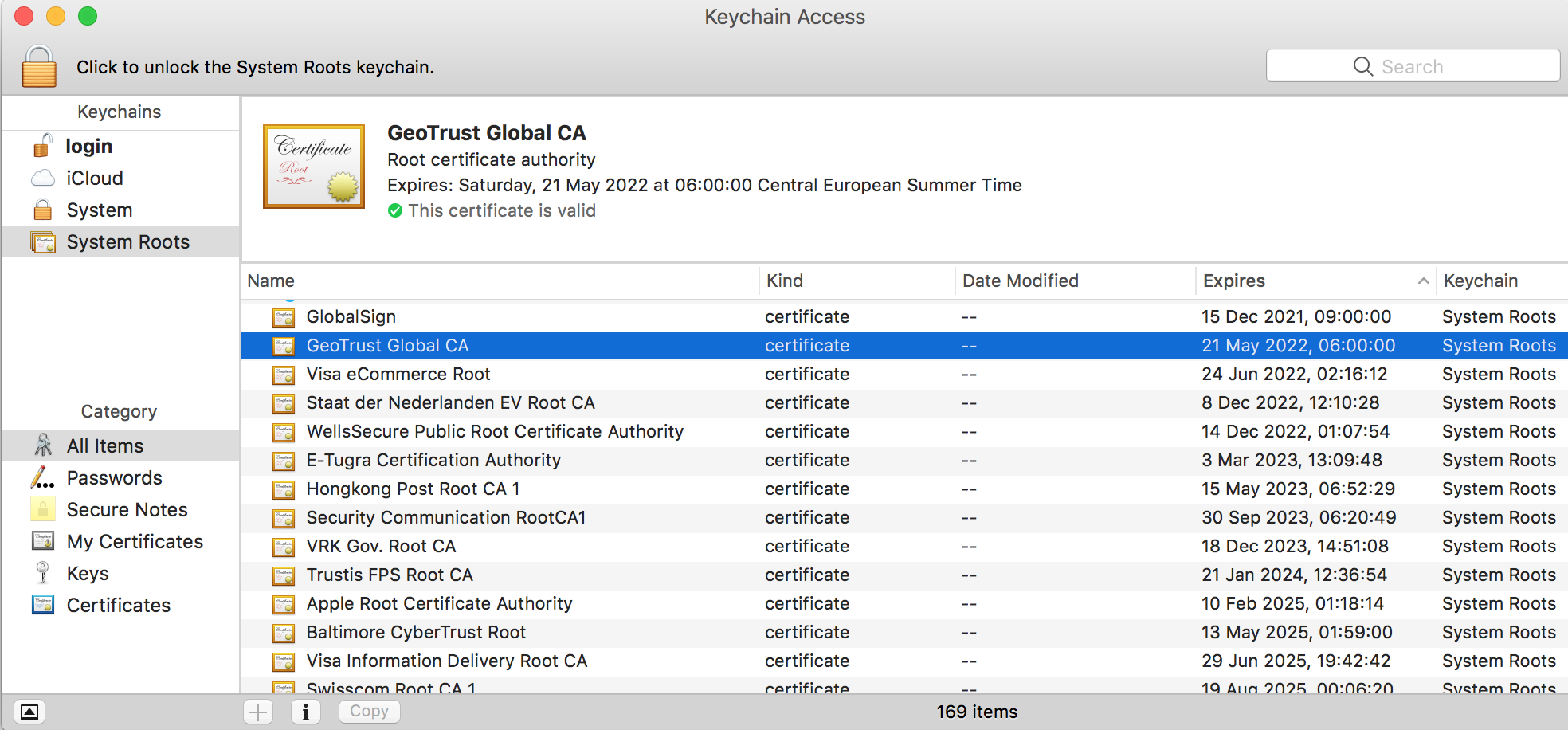

Trust store

Each client (browser, Operating System, JDK, etc.) ships with a list of trusted Certificate Authorities. This list of trusted Certificate Authorities and their public certificates are stored, this collection is usually referred to as a Trust Store.

SSL Certificate Chain

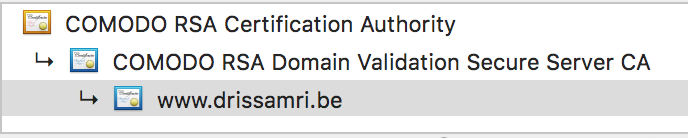

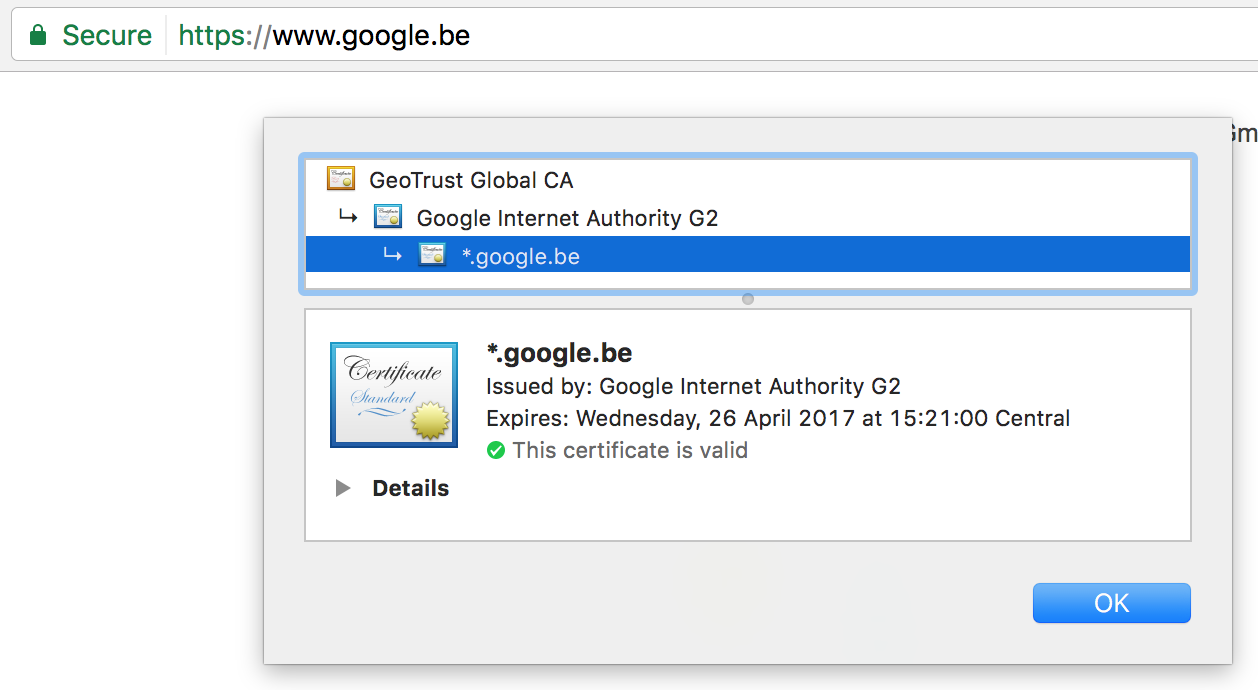

All SSL/TLS connections rely on a chain of trust called the SSL Certificate Chain. This chain of trust is established by certificate authorities (CAs) who serve as trust anchors that verify the validity of the systems being communicated with. If a certificate is signed by a certificate, that on its own turn has been signed by a Certificate Authority, you can trust the certificate because it’s in the chain of trust.

How does it work?

When you make a request to https://www.google.be, you are indicating you want to start a secured HTTP connection. The server will send its certificate (Public Key) to your browser and your browser will verify whether this certificate is trusted. To do this it will check if the transmitted certificate, or one of its parent certificates (certificate chain), is found in in the browser’s Trust Store. Here’s a screenshot from my OSX trust store, that is used by Chrome.

You can see I highlighted the GeoTrust Global CA certificate, this is the Certificate Authority used to validate my secure connection to Google:

This process is called one-way SSL authentication, in which only the server has to be validated for authenticity. This is what you will come across most of the time. Two-way SSL also exists in which the client is also required to have and send a certificate to the server. This allows the server to validate the client’s certificate.