You’ve heard about AWS Lambda and you know they have a thing called cold starts, but what are they and how bad are they? One year ago I was in this exact spot for a new project that would be built using Java, which apparently suffers tremendously from slow cold starts Let’s have a look at what I’ve learned.

What is a cold start?

AWS Lambda can dynamically scale your function from 0 instances to as many instances as you need at any given time.

This is really great since you only have to pay for the compute time you really use.

When the first requests hits your function, AWS Lambda will immediately spin up an instance of your function to handle the request.

The subsequent requests will be handled by the same instance until the load goes up, then AWS Lambda will spin up extra instances to process them fast enough.

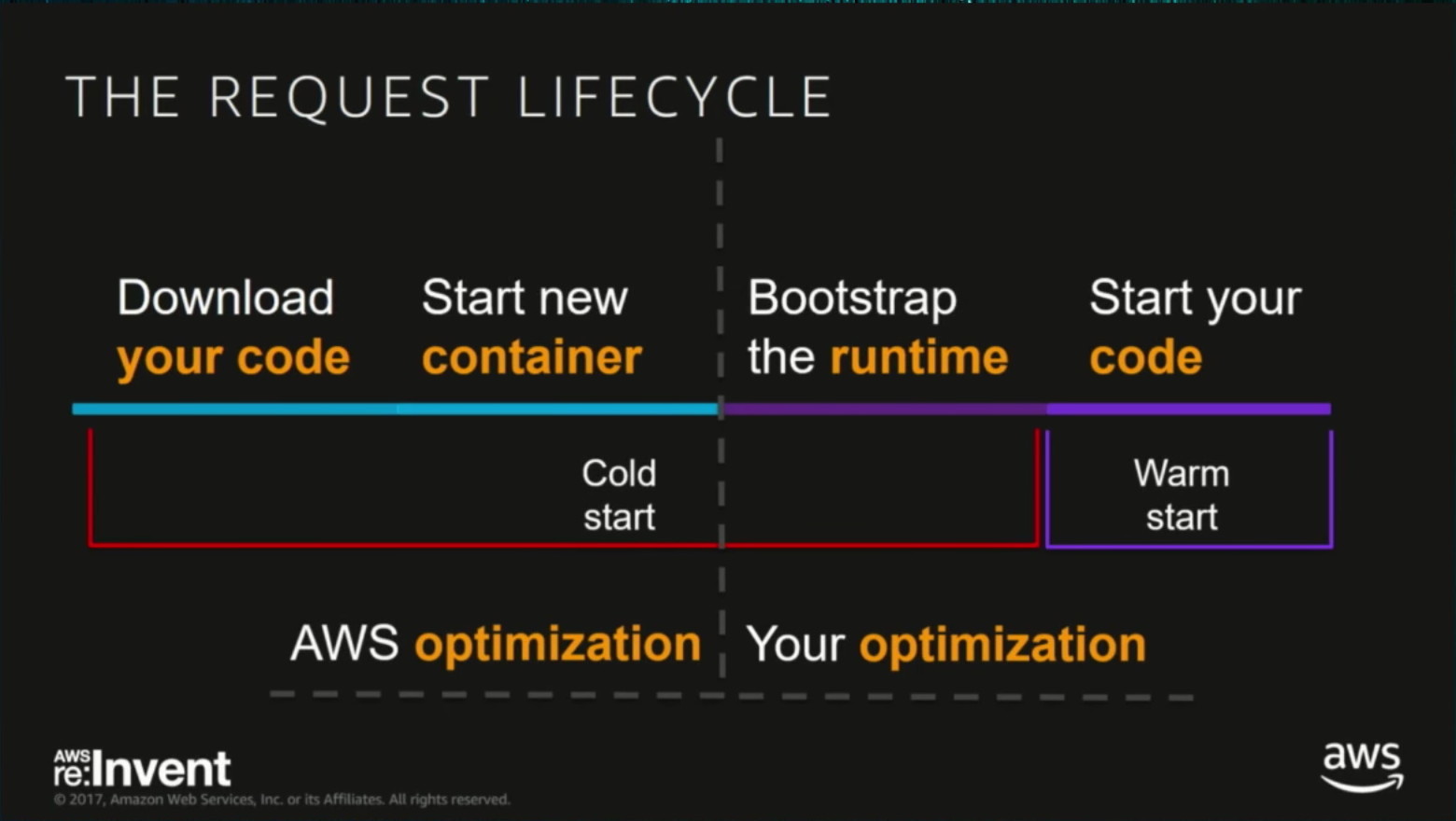

Each time AWS Lambda has to spin up an instance to process a request, that’s called a cold start, which could add several seconds to your start up. These first requests take longer to be processed, requests after this to the same container are usually referred to as warm start.

When do these cold starts happen?

It’s important to understand when these cold starts happen before we can see what we can and should do to shorten them. Here are a few examples when AWS has to spin up a new instance and go through a cold start:

- First request on your function

- Concurrent invocations

- After AWS cleans up instances

- After function deployment or configuration change

These visualization might give you a better understanding of why this is an issue.

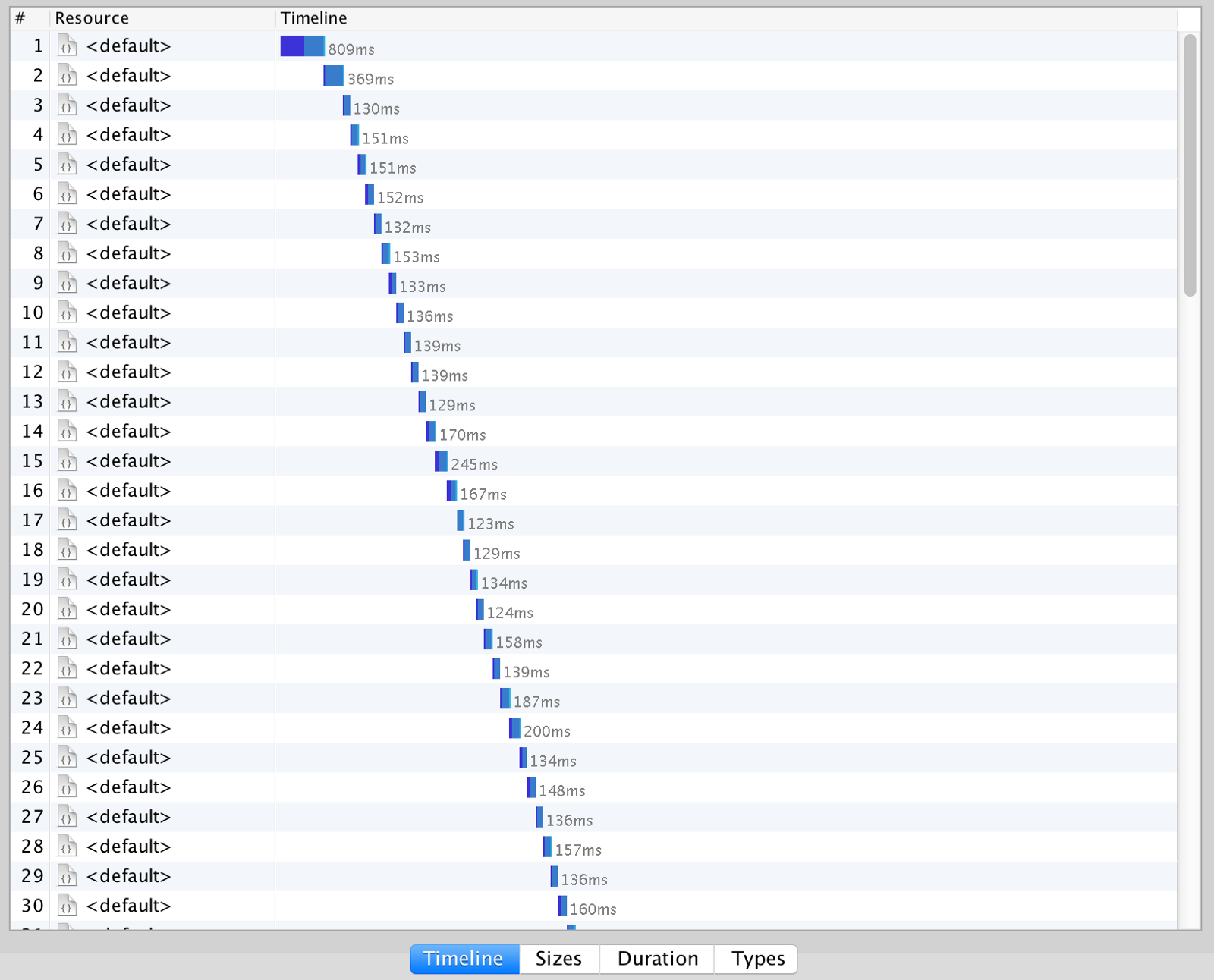

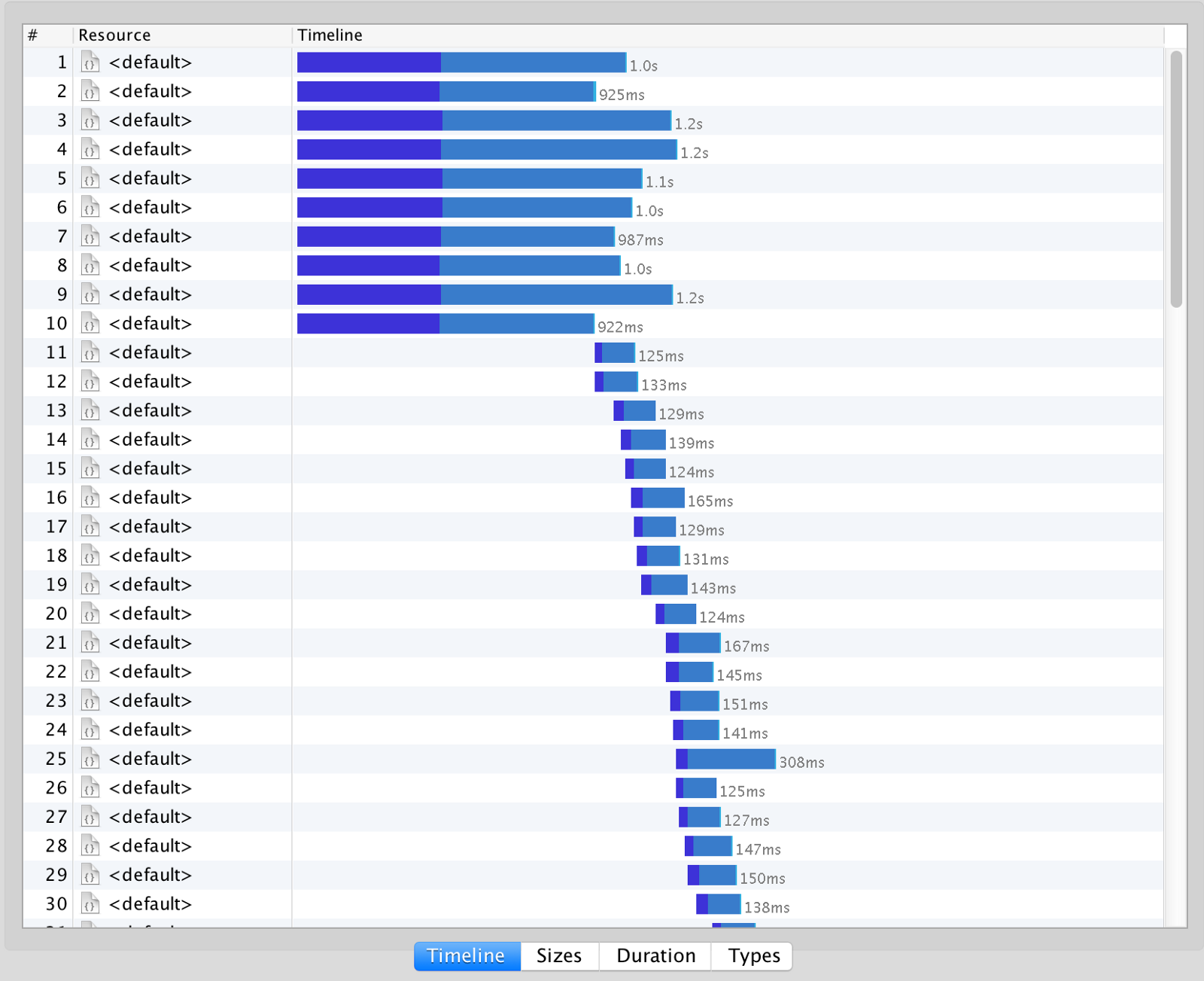

This is an example of a function that’s being called 100 times sequentially with a concurrency of 1:

Now let’s compare the same case but with a concurrency of 10:

As you can see, in the second case we’ll have 10 cold starts since AWS spins up a new instance for every concurrent request.

Are cold starts really an issue?

There are a lot of different types of applications, so understanding your use case is important before you can decide if cold starts are really an issue.

When you are building an asynchronous function, it might not be a big issue if that function takes a while to cold start. When you are building a synchronous function (REST API) it’s probably important to understand and see how big the impact could be.

Since only a small percentage of requests will lead to a cold start, it’s crucial to put it into perspective and focus on performance of warm instances. Depending on your Service Level Agreements, you should check if your 95th-99th percentile requests are making the required latency.

How do we speed these cold starts?

What can you do to make these cold starts as fast as possible? There a few things you should keep in mind:

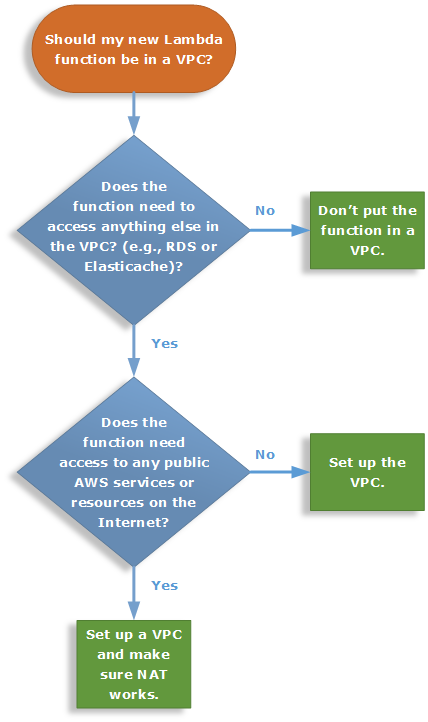

1. Avoid putting your Lambda in a VPC (Virtual Private Cloud)

In short: don’t use a VPC unless you absolutely have to.

A VPC can add up to 10-15 seconds to your function’s cold start. Yes you read that right. When you do this, an Elastic Network Interface (ENI) must be created, an IP address must be allocated to the ENI, then the ENI is attached to the Lambda. Definitely read up on the AWS documentation on this.

It’s important to note that putting your Lambda inside a VPC doesn’t make it more secure unlike it does for EC2. For EC2 you need a VPC to shield your machine from malicious traffic. Lambda functions are protected by AWS Identity and Access Management (IAM) service, which provides both authentication and authorization. All incoming requests have to be signed with a valid AWS credential, and the caller must have the correct IAM permission.

So why would you use a VPC then?

- You need to access Amazon RDS, ElastiCache, …

- You need a Private AWS API Gateway

- You need access to on-premise resources over VPN/Direct Connect

In the AWS documentation you can find a flowchart to help you decide when to use a VPC:

At re:Invent 2018 there was an excellent deep dive session - A Serverless Journey: AWS Lambda Under the Hood (SRV409-R1) - in which they announced a new architecture for VPC Lambda’s that should speed up the cold starts significantly. This should be released in 2019 but hasn’t happened so far.

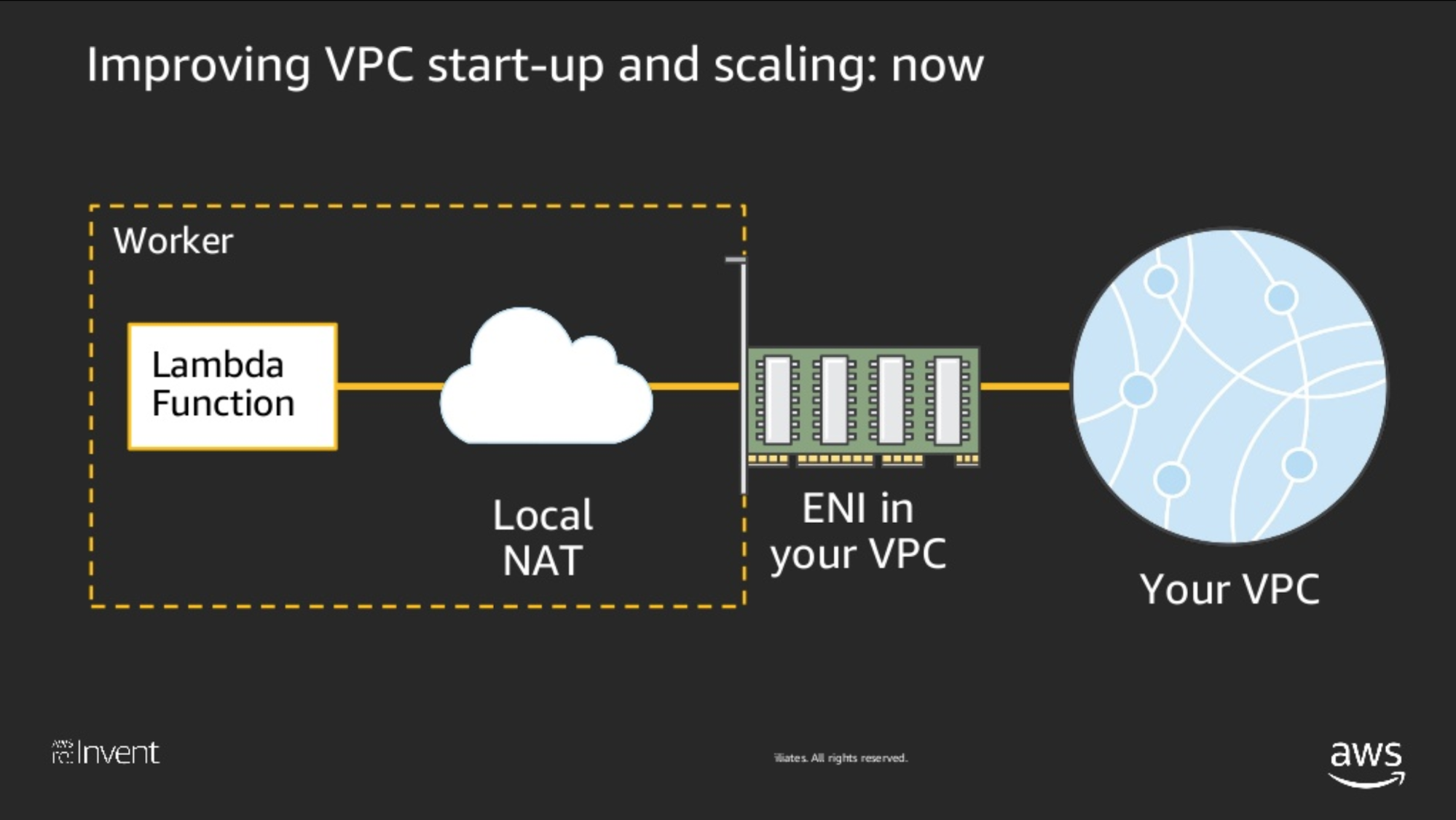

Current architecture:

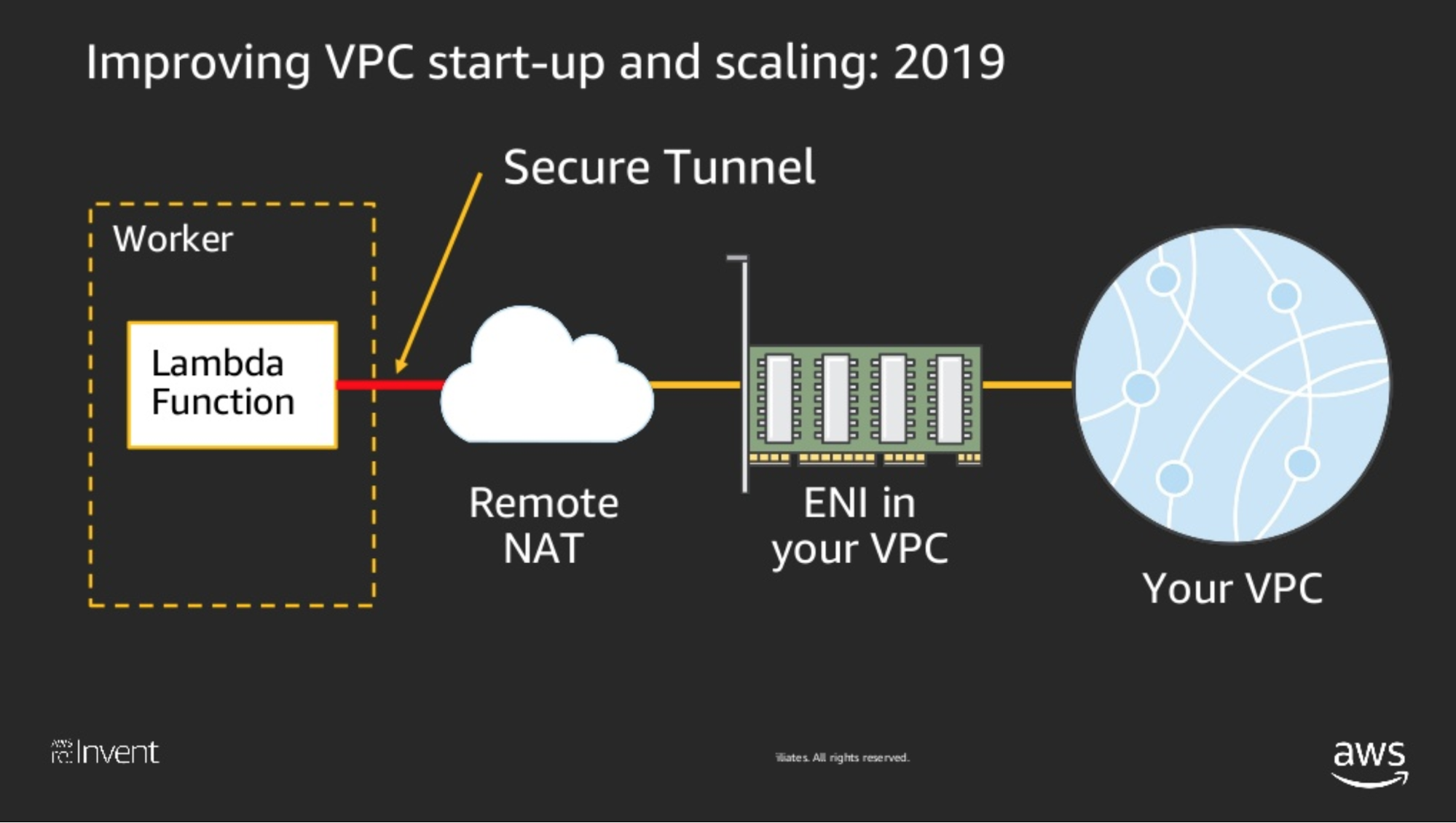

Future architecture:

2. Keep your function small and single purposed

Let your function do one thing and let it do it well. This helps you keep the codebase small and clean, which is a good design practise as well.

You can’t load what you don’t have. When your code has to be downloaded to a new instance, it’ll be faster and could potentially make initialization faster as well. When using other runtimes than Java, definitely consider minification and uglification.

3. Minimize your function’s dependencies and use lightweight frameworks

Try to minimize the dependencies you use and be critical about the ones you end up choosing.

Prefer lightweight frameworks over (slow) feature rich frameworks that contain a lot of things you don’t need. Your default toolbox as a Java developer most likely contains Spring, even though Pivotal is working hard to optimize startup, If you really want to use Spring, definitely make sure you use Spring Cloud Function instead of Spring Boot. A lot of optimalization work has been done lately to make it faster.

When integrating with AWS services like S3, DynamoDB and so on it helps to use the AWS SDK for Java 2.x over the older one. This can shave off a few hundred milliseconds from start up. AWS provides a no-dependency lightweight HTTP client that starts up faster than the default Apache HTTP client, but this is not enabled by default.

Most of my Lambda’s are built with Dagger (Dependency Injection) and Gson (JSON parsing, faster than Jackson) and a few extras. This has served me well so far but I’m evaluating newer frameworks like Quarkus and Micronaut that have been built with fast start ups and low memory environments in mind. Both these frameworks have been fast to provide initial support for GraalVM, which I won’t talk about today but this will the subject of my next blog post.

4. Prefer low overhead runtimes

Dare to ask if your services could be implemented in a language that has less problems with slow cold starts like node.js, Python or Go.

Java is still my go-to language but functions should be small services, which could help in experimenting with other languages. Nowadays the JavaScript quirks are much less when using node.js with TypeScript. This could be a good candidate for a Java developer to experiment with.

5. Choose the right memory settings

The higher you set the memory settings, the more you are billed for execution time. The important remark is, when you double your memory on AWS Lambda you get more than double the CPU capacity. This could possibly mean your Lambda will execute faster and it’ll cost less than you would have with lower memory settings.

It’s crucial to fine-tune and find the best memory settings for your function. A tool like AWS Lambda Power Tuning could help you do this automatically.

6. Move state to static variables & Singletons

Anything initialized in static blocks and global variables outside your function code will be reused for all subsequent requests to that instance. This is why it’s smart to move objects that are expensive to create to global state or use singletons. Definitely do this for all connections.

Real function cold starts examined

When comparing different languages and frameworks, it’s important to do more than a Hello World example.

Especially in Java adding one dependency could potentially have a big impact on your start up already depending on what gets initialized.

I will build a simple example that’ll use an API Gateway that has one HTTP endpoint addProduct that’s backed by a Lambda function.

This function will add a new product in a database. The database we use in this example is DynamoDB, since it’s very easy to setup and easy to connect to from a Lambda.

I’ll have a look at this example implemented with a few different frameworks and use X-Ray to examine the cold start performance.

The example’s architecture is shown below:

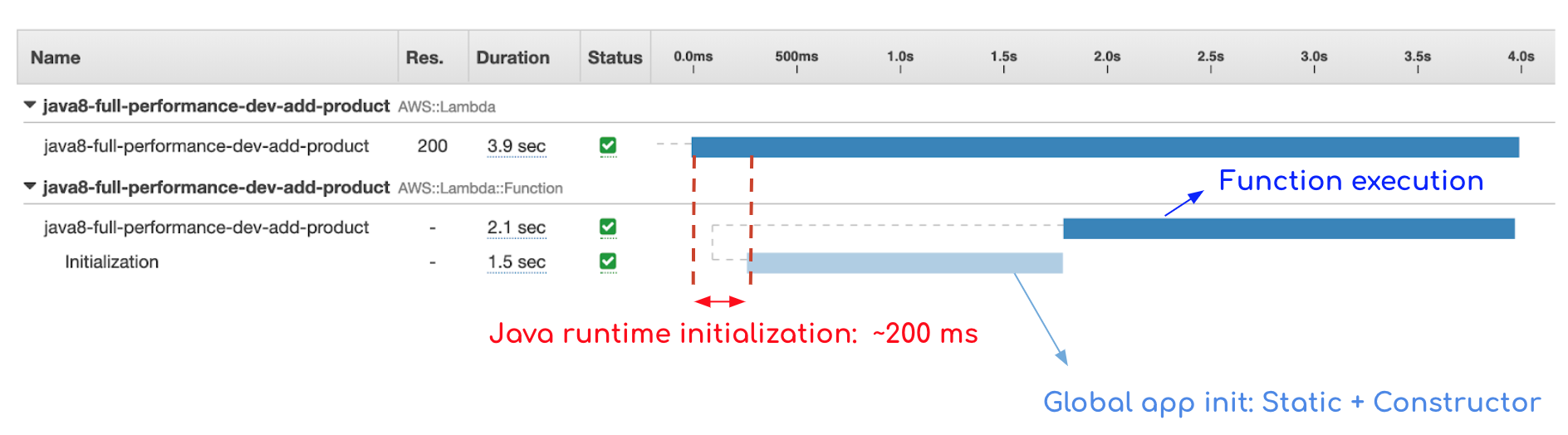

When inspecting your Lambda with AWS X-Ray you can get a good understanding of the different phases of the instance start up.

After your function was triggered, you can check CloudWatch Logs to see how long your function ran and how much you time you are billed for:

REPORT Duration: 2170.02 ms Billed Duration: 2200 ms Memory Size: 1024 MB Max Memory Used: 158 MB

The most important fact I learned while doing this, is that the reported duration is NOT how long your function needed to actually complete.

This is the time how long your code inside the handle method needed to finish. All the time your function needed to initialize like logic

in your class Constructor, static initializers and global variables are not shown in the reported duration.

When a framework does all its heavy lifting in the constructor, you could potentially see a low reported duration in CloudWatch while the actual duration could’ve been much higher.

This is why it’s important to compare actual end to end duration instead of the reported duration in CloudWatch to have a fair comparison.

Example: Java 8 - Spring Cloud Function

Last time I’ve used Spring Cloud Function 1.x the cold start times were terrible (8-12 seconds). These cold start times however should have drastically improved in recent updates by providing a more functional bean style registration among other things.

I made a few attempts to see how much they have improved but I kept running into issues, with both my own example as well as the Spring Cloud Function AWS reference sample.

My test case ended up with an exception which can be found below - the same issue was reported on GitHub issues:

01:32:42 |_ checkpoint ⇢ Request to GET http://localhost/2018-06-01/runtime/invocation/next [DefaultWebClient]

01:32:42 Caused by: java.net.ConnectException: Connection refused

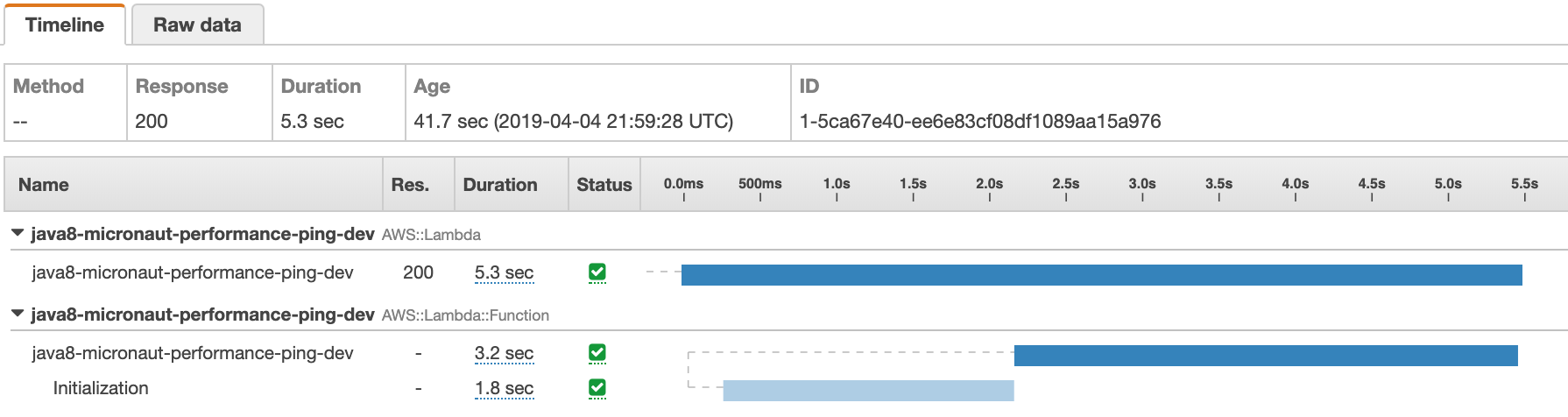

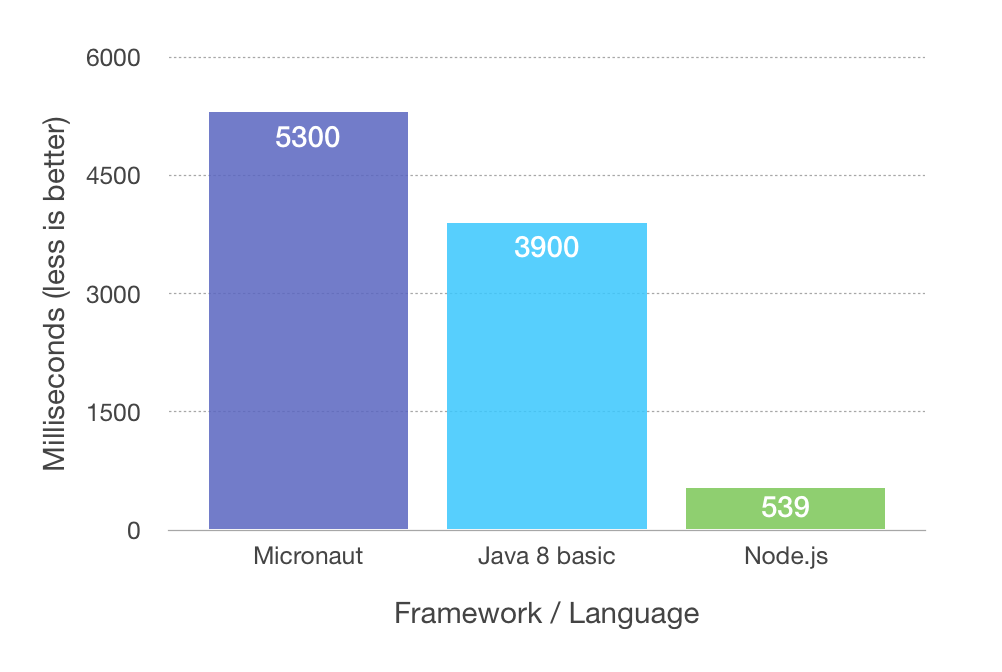

Example: Java 8 - Micronaut

In this example I got to play around with Micronaut, a young new promising Framework that also has good support for Serverless applications.

- Micronaut 1.x

- AWS SDK 2.0: Integration with DynamoDB + lightweight AWS HTTP client

Cold start: 5.3 seconds

CloudWatch REPORT Duration: 3210.99 ms Billed Duration: 3300 ms Memory Size: 1024 MB Max Memory Used: 172 MB

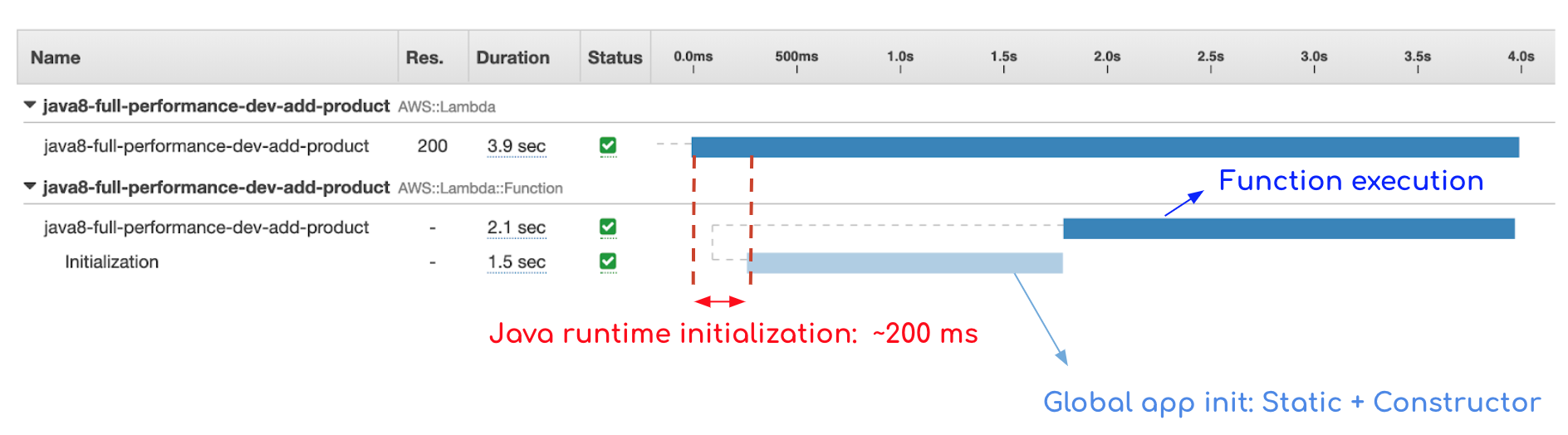

Example: Java 8 - basic

This example is how I usually built Lambda’s in the last year.

- Dagger 2: lightweight compile time dependency injection

- Gson: fast startup JSON processing - faster than Jackson

- AWS SDK 2.0: Integration with DynamoDB + lightweight AWS HTTP client instead of the Apache default

Cold start: 3.9 seconds

CloudWatch REPORT Duration: 2170.02 ms Billed Duration: 2200 ms Memory Size: 1024 MB Max Memory Used: 158 MB

Example overview

While this is not perfect, for asynchronous requests this acceptable in most cases. For synchronous requests it still might be good enough, since only a small % of total requests will actually encounter a cold start. This will definitely improve in the future. Hopefully, when AWS releases the JDK 10 runtime it’ll include some noticeable improvements already.

When this is not acceptable for one of your low latency critical services I’d really suggest to take a look at node.js, especially combined with TypeScript, which should be reasonably fast to be picked up by your Java developers. One of the benefits of Lambda’s is that the code base for one function should never be too big, so you can easily experiment and try to use another framework or language for a small part of your overall architecture.

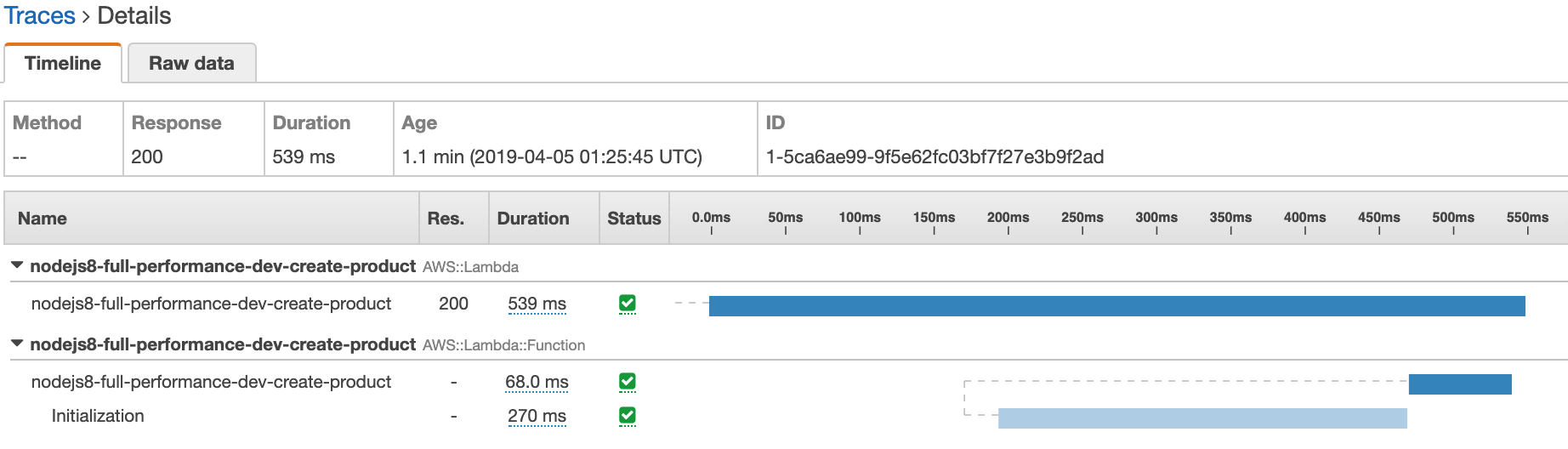

Let’s have a quick look at the same example implemented in node.js 8.

Example: node.js v8.10

- node.js 8 + TypeScript

- webpack: minification, uglification & tree-shaking

- Middy middleware framework

- DynamoDB SDK

Cold start: 539 milliseconds

CloudWatch REPORT Duration: 69.36 ms Billed Duration: 100 ms Memory Size: 1024 MB Max Memory Used: 106 MB

Conclusion

An overview of the three different working examples. The results of Spring Cloud Function are omitted because of the issue we discussed above.

Java will never have the fastest start up times, but you can optimize quite a bit. Make sure you pick your dependencies & frameworks carefully. Tweak & experiment with memory settings depending on what your functions do. Default to Lambda’s outside of a VPC, unless you really need to. When the highest start up performance is needed, be open to experiment with a different language like node.js.

We haven’t spoken about the AWS Lambda Custom Runtimes, but they open up some more possibilities to tweak the JVM settings or to deploy an experimental GraalVM native-image. In my next post I will do the same test with a GraalVM native-image, see how the performance measures up and what limitations it has.